Pomodoro Experiment: A 4-Day Comparison Of Focus and Productivity

The Pomodoro Technique was created with the aim of using time as a valuable ally to accomplish what we want to do the way we want to do it, and to empower us to continually improve our work or study processes.

~ Francesco Cirillo, Creator of the Pomodoro Technique [3]

TLDR

I conducted an experiment on the Pomodoro Technique, a method that breaks work into 25 minute intervals separated by short breaks.

Over four workdays, I compared my regular work routine with Pomodoro days. I collected data on tasks completed, self-rated focus, perceived productivity, and a reaction speed test.

My findings suggested that I felt more focused in the mornings regardless of technique. Yet, the Pomodoro Technique helped sustain my focus and productivity into the afternoon. While the technique occasionally interrupted flow with breaks, I found it beneficial and plan to continue using it.

I still have questions about the optimal work-break split and whether Pomodoro was solely responsible for my sustained focus.

Introduction

The Pomodoro technique is a time management method to strengthen focus. You set a timer for 25 minutes to work, followed by a 5 minute break. Every 4 of these cycles, you take a 20 to 30 minute break. [1]

I want to figure out if this technique really works for me. So in the spirit of my newfound skepticism, I've decided to apply some scientific thinking. I'm curious to see how this technique really effects my focus, so I've created an experiment to test it out.

Research

The Pomodoro Technique:

The original method uses six steps:~ Wikipedia [1]

- Decide on the task to be done.

- Set the 25 minute timer.

- Work on the task.

- End work when the timer rings, take a 5 minute break.

- If you have finished less than 3 Pomodoros, go back to step 2.

- After 3 Pomodoros are done: Do 1 more 25 minute focus timer. Then take a 20 minute break. After the break is finished, return to step 2.

The Wikipedia article continues with some more information about the original technique:

A Pomodoro is indivisible; when interrupted during a Pomodoro, either the other activity must be recorded and postponed ... or the Pomodoro must be abandoned.

~ Wikipedia [1]

I don't expect to be interrupted during the experiment, but I do expect to be distracted. From the looks of things, whenever I hit a distraction I should write it down and look into it during the break.

I think it's interesting to have this ultimatum within the Pomodoro framework. I have seen other similar ultimatums used to help with self discipline before. For example,

You're allowed to switch your task, but you aren't allowed to go back to your previous task. Whatever you've already invested in your previous task is gone. It's this or nothing. ... If you're an author or a programmer, you can start writing a new book or designing a new app, but only if you permanently delete the previous draft of code.

~ Martin Meadows: Self-Disciplined Producer [2]

What happens if you complete a task before the timer runs out? The paper [1] provides four options:

- (Not Explicitly stated) Start the next task.

- Review completed work.

- Review what you've learned, and see if you had met your goals.

- Review the list of upcoming tasks, and update them.

Finally, to use the technique effectively, it requires maintaining a prioritized to-do list and recording completed tasks for that sense of accomplishment. [1]

The Original Paper

All of my information about the Pomodoro technique to this point came from half page blurbs in productivity books and through word of mouth. I was able to find the original paper [3], written by the creator of the technique, on how to use it.

Unfortunately for me, I had found it after I conducted the experiment. The following is some additional context on the technique, and things that are not included in the brief blurbs and wiki articles:

Background:

The Pomodoro Technique was born out of Francesco Cirillo's challenge to truly study for just 10 minutes at a time. Inspired by a tomato-shaped kitchen timer (pomodoro is 'tomato' in English), he began developing this technique in the late '80s while in college. [3] The paper I refer to here was published in 2006, before smartphones became ubiquitous and brought their distractions along.

Context:

Cirillo developed the Pomodoro Technique based on several principles:

- Viewing time as linear and measuring time cause anxiety (deadlines, being late, etc.)

- Using the mind and body more optimally allows us to think better, learn faster, and achieve clearer focus

- Simpler tools allow for more concentration on the task at hand, rather than managing the tool itself

Stages:

The Pomodoro Technique is comprised of 5 stages:

~ Francesco Cirillo [3]

- Planning: Deciding the day's activities

- Tracking: Recording the amount of effort(pomodoros) for tasks

- Recording: Archiving and reflecting on how the information tracker

- Processing: Reflecting and considering the data recorded

- Visualizing: Understanding and viewing the information from a different perspective

Cirillo specifically states that using a physical kitchen timer, coupled with paper and pencil, seems to work better than a software-based timer. The ticking sound and the noise made by the kitchen timer, he believes, contribute to the mentality of the technique. However, he clarifies that it's not obligatory, especially if others might be annoyed by the ticking.

Objectives:

The Pomodoro Technique has five primary objectives:

- Determine the effort an activity requires

- Minimize interruptions

- Estimate the effort needed for activities

- Enhance the effectiveness of the Pomodoro

- Create a timetable

Rules:

In addition, there are 9 rules to the Pomodoro Technique:

~ Francesco Cirillo [3]

- A Pomodoro consists of 25 minutes Plus a 5 minute break

- After Every 4 Pomodoros Comes a 15-30 minute break

- If a pomodoro Begins, it has to ring

- If a pomodoro is interrupted definitively (can't be handled) the pomodoro is voided and won't be recorded

- If an activity is compiled once a pomodoro has already begun, continue reviewing the same activity until the Pomodoro rings

- Protect the Pomodoro. Inform effectively, negotiate quickly to reschedule the interruption, call back the person who interrupted you as agreed.

- If it lasts more than 5-7 Pomodoros, break it down. Complex activities should be divided into serval activities.

- If it lasts less than 1 pomodoro, add it up. Simple tasks can be combined.

- Results are achieved pomodoro after pomodoro

- The next pomodoro will go better

Why 25 Minutes?

The Pomodoro Method is well-known for its use of a 25-minute focus period followed by a 5-minute break. The reasoning behind this specific duration is intriguing:

- 25 minutes of work plus a 5-minute break totals 30 minutes, which makes a Pomodoro—defined as a work period plus a break—an exact half hour. This consistency simplifies estimating and planning.

- 25 minutes is a short enough span to reasonably delay any distractions that arise until the end of the work period. So, if someone interrupts you during your Pomodoro, you don't need to feel pressured to abandon your focus time to address the interruption.

- Cirillo cites a study indicating that focused sessions lasting 20 to 45 minutes, followed by a short break, maximize attention. [3]

In various work groups which experimented with the Pomodoro Technique in mentoring activities, each team was allowed to choose the length of their own Pomodoro on the condition that this choice had to be based on observations regarding effectiveness. Generally, the teams started off with hour-long Pomodoros (25 minutes seemed too short at first), then moved to 2 hours, then down to 45 minutes, then 10, till they finally settled on 30 minutes.

~ Francesco Cirillo [3]

Cirillo eventually settled on 25 minutes as the duration for a Pomodoro, though he does note that the ideal time lies somewhere between 20 and 40 minutes.

Regarding breaks between work sessions, a more stringent limit of 3 to 5 minutes is set, extending to 10 minutes only on particularly exhausting days. This is based on the belief that breaks longer than this disrupt the rhythm of work.

After every 4 Pomodoros, a longer break of 15 to 30 minutes is recommended. It's interesting to note that breaks exceeding 30 minutes are thought to disrupt the rhythm and make re-entry into work mode more challenging.

Pomodoro To-Do List

Cirillo spends roughly half of his time in the original paper [3] discussing the to do list system of the pomodoros. Yet, other sources that recommend the technique rarely ever mention it.

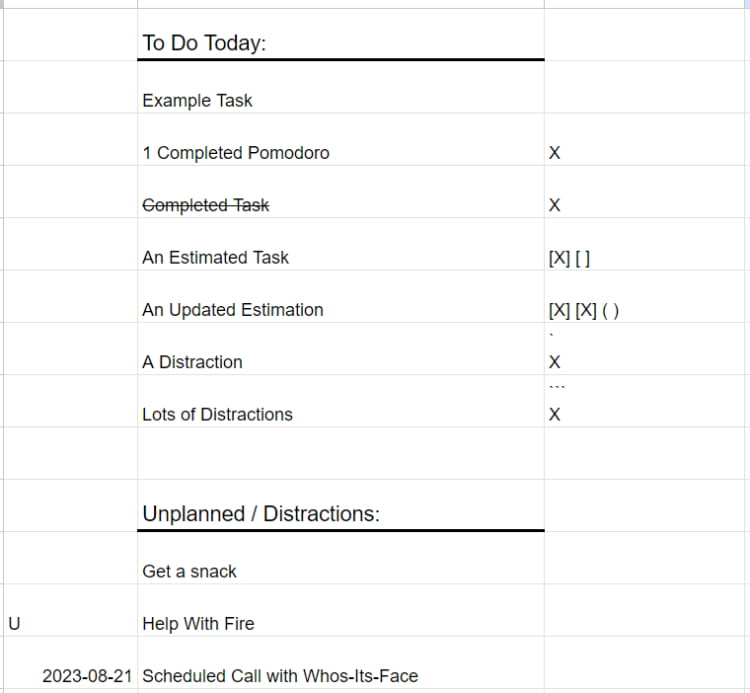

The Pomodoro To-Do list system is essentially an enhanced traditional checklist. Here's an illustration of the various notations:

A rough illustration of the different aspects of the Pomodoro To Do List System.

A rough illustration of the different aspects of the Pomodoro To Do List System.

- The left column is for marking unplanned activities (noted with a 'U') and deadlines for distractions or unplanned tasks.

- The middle column houses the planned task list at the top, followed by an unplanned task list below.

- The right column keeps track of completed Pomodoros (marked with an 'X'), estimated task durations (denoted by squares), updated estimates (indicated by circles), and a tally of interruptions (noted with ').

The unplanned task and interruption list helps you record distractions for later attention. It's suggested that once enough disruptions accumulate, you set aside a Pomodoro's worth of time to address them.

This is a broad overview of the system's notation. If you're interested in implementing this system, I'd recommend reading through the original paper for more details. [3]

Critiques of the Technique:

So far, here is a list of most of the criticisms and critiques I have found of the Pomodoro Method:

- The time limits get in the way of work [4] [5] [6]

- The technique isn't useful for all jobs, or types of tasks [4] [5] [6]

- The technique focuses too much on the time spent on tasks, rather than focusing on completing the tasks. [5]

- Is the technique needed, or is it extraneous? [6]

- The technique interferes with teamwork communication. [6]

Hypotheses

Pomodoro Hypothesis: Using the Pomodoro Technique will improve my hourly productivity, and alertness throughout the day.

Null Hypothesis: Using the Pomodoro Technique will have no effect on my hourly productivity or alertness throughout the day.

Study

I have 5 workdays that I can use for this experiment before I leave for a trip. I will be dividing these days into 2 groups: Pomodoro days and Control days.

Groups

Control group: 2 randomly selected workdays where I will be working as I normally do. I won't be using any specific timed work technique. I am allowed to

Randomly selected days: 1 (Monday), 4 (Thursday)

Pomodoro group: The 3 remaining workdays. These days I will use the technique, and follow it as closely as I can to its original design. I will be using my Productivity Bar app to keep track of the sessions.

Days: 2 (Tuesday), 3 (Wednesday), 5 (Friday)

Control Variables

1. My sleep schedule will remain exactly the same throughout the entire week. Waking up and Going to bed at roughly the same time each day. Waking up at 7:30am and going to bed at 11pm.

2. The hours that I work will be exactly the same each day. 11am -> 5pm, 6 hours a day.

3. My work environment will stay the same each day. (My desk in my room, 2x 32 inch monitors, clean desktop space.)

4. My routine will stay as similar as possible from day to day.

5. I will be powering off my phone and putting it in my closet during the workday. I will get 2 times to check it, at 2 hours in (1pm), and 4 hours in(3pm). I will have my apple watch on Do Not Disturb as well, but I will have a vibration only alarm every hour for the data collection.

Data Collection

Every hour, during both types of days, I will be recording the following:

- The number of tasks completed (cumulatively for the day)

- A self-rating of focus on a scale of 1-10.

(For my own mental notes: the 1-10 rating will work as follows: 1 = focused 10% of the hour, 5 = focused 50% of the hour, 10 = focused 100% of the hour) - A self-rating of my perceived productivity on a scale of 1-10.

(10 = I felt like I was at my most productive, 5 = moderately productive, 1 = not productive.) - A reaction speed test. I will take the average of 3 reaction speed tests for this score. I will be using The Human benchmarks: Reaction Time Test.

Results

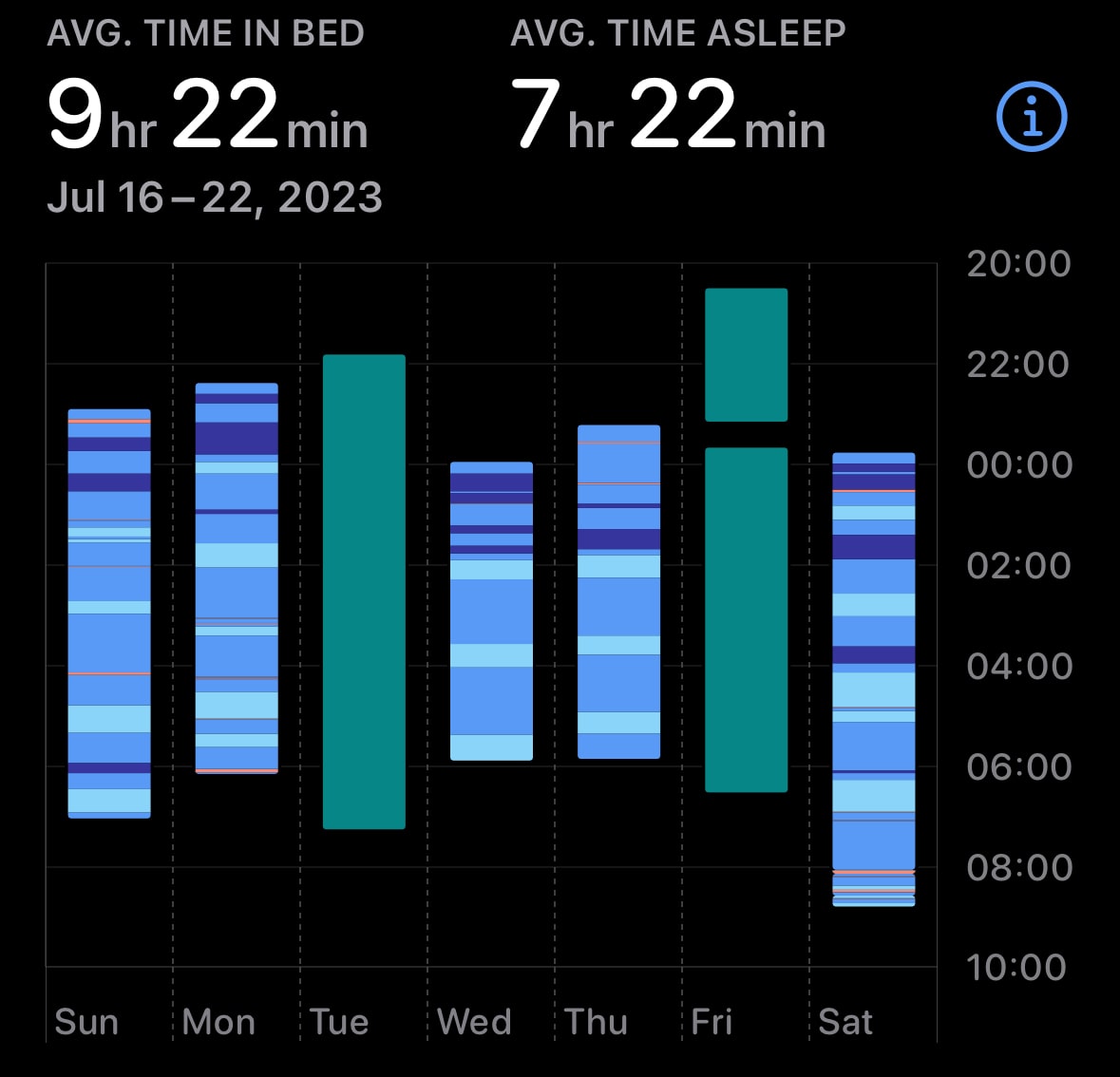

I tried my best to control as much of the factors that I could consider for this experiment. I maintained roughly the same schedule every day. I had the same snack at the same time. Started everyday with a short 10 minute walk. I worked at the same times, and 'controlled' for exercise. (aka, I didn't exercise). I kept my phone powered off, and only checked it every 2 hours. I also tried keeping my sleep as consistent as possible:

Sleep Stats From Apple Watch. Monday represents the sleep I got Sunday night, which effects Monday's performance.

Sleep Stats From Apple Watch. Monday represents the sleep I got Sunday night, which effects Monday's performance.

However, what the sleep chart doesn't show is that I went to bed at around 2 am on Thursday night, which meant that Friday was already off to a challenging start. I ran into further problems during the day on Friday, so I decided to cut it from the experiment because of how much it effected my ability to focus and just exist.

One interesting outcome from this experiment is how much of a difference I felt just by trying to get consistent sleep and powering off my phone. There's a significant chance that maintaining a consistent sleep routine and removing phone distractions had a greater impact on my feelings of focus and productivity than the Pomodoro technique itself.

Nevertheless, during the four days of the experiment (Monday through Thursday), all conditions remained consistent, allowing me to more clearly observe any differences. As a reminder, Monday and Thursday were control days, while Tuesday and Wednesday were designated Pomodoro days.

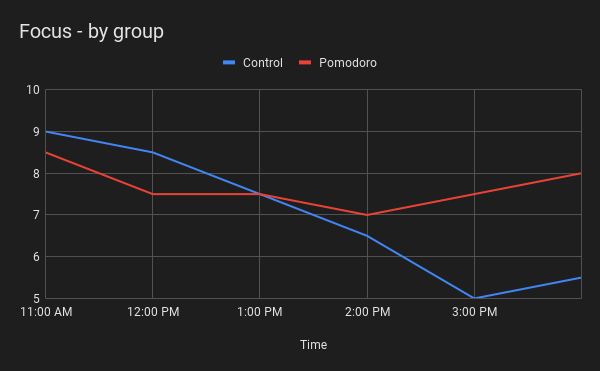

1) Self Reported Focus:

Self reported focus averaged by group. 1 = focused 10% of the hour, 5 = focused 50% of the hour, 10 = focused 100% of the hour.

Self reported focus averaged by group. 1 = focused 10% of the hour, 5 = focused 50% of the hour, 10 = focused 100% of the hour.

The biggest difference between the control and pomodoro days was in the afternoon. After around 2pm on control days there was a noticeable fatigue. Concentration became challenging, and I found myself paying more attention to distractions.

However, on Pomodoro days, I didn't notice this dramatic slump in the afternoon. The mornings were slightly less effective compared to the control, but I wasn't feeling nearly as slumped compared to the control.

Another noticeable difference was in the first 2-3 hours of work. On control days, when there was no predetermined break schedule, I worked straight through the first one or two hours without significant breaks. On Pomodoro days, I took two 5-minute breaks within each of the first hours. These breaks felt somewhat unnecessary, striking just as I was beginning to enter a state of deep focus.

I am typically someone who is able to get more done in the mornings, so I wasn't surprised that I felt more focused in within the first 3 hours. I've also dealt with this afternoon slump in energy for a long time, so I wasn't too surprised to see it again here.

Across all four experiment days, I felt more focused in the mornings than ever before. This may be due to my excitement to conduct this experiment, and having an interesting challenge at work. Or that I was getting reasonable and consistent sleep, and have tried my best to power off my phone and remove distractions. Regardless, the experiment days seemed to have elevated my ability to focus.

Pomodoro days had a longer, more sustainable burn, while the control days had more of a burst-and-burn pattern. Although the afternoon decline on control days returned my focus to a mediocre or poor level, I retained some focus. I could still accomplish tasks, albeit at half (or less) of my morning focus level.

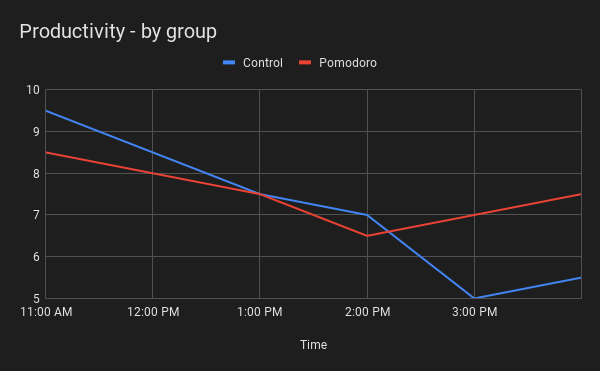

2) Self Reported Productivity:

Self reported productivity averaged by group. 10 = I felt like I was at my most productive, 5 = moderately productive, 1 = not productive.

Self reported productivity averaged by group. 10 = I felt like I was at my most productive, 5 = moderately productive, 1 = not productive.

Productivity and focus usually go hand in hand, but there were times when I felt focused without being productive.

I initially recorded the number of tasks I completed per hour as a form of measuring productivity. But then I realized that the challenge, time and effort of each task was wildly unequal. On the first 2 days, (1 control day, and 1 pomodoro day) I had a pretty consistent task list that felt roughly equal. But I started a somewhat sizable refactor on the 3rd day that ended up taking a decent chunk of the 4th day to finish.

So what in my mind, was originally a single task, ended up spanning roughly 2 days. So I am glad I keep the self-reported productivity measurement during the experiment.

All in all, the self-reported productivity seemed to be closely tied to my ability to focus during that hour. The less I was distracted, the more I felt I was getting done.

Again, the mornings felt more productive on the control days, yet not by much. The afternoons felt significantly more productive on pomodoro days, rather than control days.

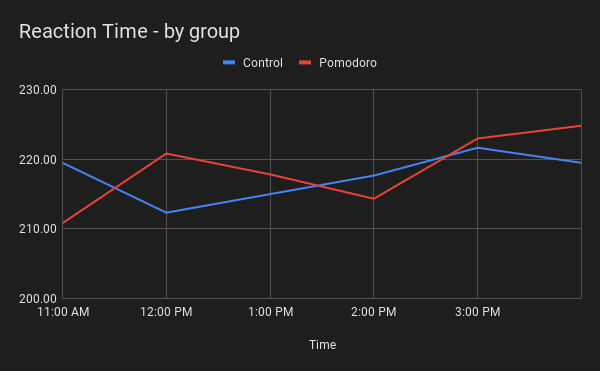

3) Reaction Time:

The average reaction time of 3 tests, averaged by group. (Reminder: Faster Reaction Time = Smaller Time)

The average reaction time of 3 tests, averaged by group. (Reminder: Faster Reaction Time = Smaller Time)

I'm going to be completely honest. I started this experiment thinking that my reaction time would be a great way to test my alertness or ability to focus throughout the day. Something that was a 3rd party way to test the Hypotheses, that would at least show me something.

But when I was conducting the experiment, the reaction time felt almost completely random. In fact, I felt as if I was playing it like a game, and finding things that impacted my reaction time outside of the controlled variables, or even the independent variables.

I learned pretty quickly to turn off all music, look at a specific part of the screen, and hold my finger in the same spot, because any of these things impacted my reaction time.

The reaction time results didn't seem to be correlated to one group or the other, or depend on how I physically or mentally felt. There were times where I was getting the fastest reaction times I had gotten, during the time I felt the mentally slowest and unable to think.

Even after taking the reaction test 3 times, and averaging the scores, I felt as if it wasn't correlated with much. Which was kind of a good thing, it reminded me that sometimes things just aren't correlated.

After this experiment, I doubt that whether you use the pomodoro technique or not effects your reaction time. Yet if I were to conduct the experiment again, I would have tried using a different reaction time test.(But each time you take it, takes 5 minutes. Which would have effected the study.)

Discussion

There were a number of things that I had learned about the overall experiment process by doing this. I originally avoided researching into the technique, and the criticisms out of a fear of becoming more biased. Which I thought might play a role in how the experiment went.

Looking back, I think this fear was misplaced. There was a lot of depth in the pomodoro technique that I didn't even know about. There were a lot of thought provoking critiques, that would have changed what I measured in the experiment. In the future, I will be doing a lot more research into these opposing views before I conduct any experiment.

After conducting the experiment, and doing the research of the more in-depth technique and its critiques, I feel I have a better appreciation for both sides.

I experienced first hand, some of the points that the critics make. In the mornings, when I am traditionally more inclined to focus, taking a 5 minute break after 25 minutes breaks my flow. There were times where I felt that the technique got in the way, and there were times where I felt like it was saving my butt.

I definitely feel as if the pomodoro technique helped me sustain my focus for a longer period of time. I would say that over the course of the day, this improvement was much more than what was lost by working in 25 minute chunks.

Additionally, in the afternoons I felt like the 5 minute breaks were more rewarding and rejuvenating than during the morning. When I was 20 minutes into a pomodoro, I felt much more motivated to work the final 5 minutes, knowing that I had a break to look forward to.

I also felt that the longer breaks every 4 pomodoros helped sustain me over the course of the day. I didn't feel guilty about them, and by the end of the day I got more done with the breaks, than I would have without them.

Overall, I feel like I have a much more nuanced appreciation for the technique, as well as a few more questions than answers.

Some more questions:

- What difference would the to do list aspect of the pomodoro technique have made?

- Is the pomodoro technique responsible for my sustained focus in the afternoons? Or was something else responsible for this effect?

- What happens after 6 hours of work? Does the pomodoros' sustained focus die off at a specific time?

- Is the 25-minute work/5-minute break split optimal? Would varying the ratio be more impactful?

Since this experiment, I've been using the pomodoro technique and task list system for writing and personal projects. Sometimes I take longer breaks, and other times I don't take breaks at all. In the end, I feel like I'm much more focused, and the difficulty of just starting to work is a lot lower.

I'm not sure if I'll use it forever. So far I've noticed a positive impact on the key elements I had difficulty with when working. I still believe in the core ideas behind the pomodoro technique: Making better use of the mind and body help us to accomplish more, and that the next time will go better.

Footnotes:

- abcde Wikipedia: Pomodoro Technique

- a Martin Meadows: Self-Disciplined Producer

- abcdefghi Francesco Cirillo: The Pomodoro Technique* 45 page paper by the creator of the Pomodoro technique, detailing how it works

- ab Quora: What are some criticisms of the Pomodoro Technique?

- abc Produvtivityist: The Problem With the Pomodoro Technique

- abcd infoQ: A Critique of the Pomodoro Technique

- Zhighley: The Danger of the Pomodoro Method